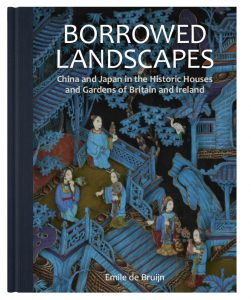

Borrowed Landscapes

China and Japan in the Historic Houses and Gardens of Britain and Ireland

The art and ornament of China and Japan have had a significant impact on European material culture over the last 500 or so years, leaving traces in many country houses and gardens. East Asian luxury objects were brought to Europe through trade from the sixteenth century onwards. Products such as porcelain, lacquer and embroidered silk were considered highly desirable and were rapidly incorporated into European interiors. Asian artisans responded by producing objects specifically for the European market. East-Asian objects also began to be adapted, dismembered and remounted by European artisans, to suit European customs and perceptions. Furthermore, objects started to be made in Europe in emulation of East-Asian materials, surfaces and motifs.

The art and ornament of China and Japan have had a significant impact on European material culture over the last 500 or so years, leaving traces in many country houses and gardens. East Asian luxury objects were brought to Europe through trade from the sixteenth century onwards. Products such as porcelain, lacquer and embroidered silk were considered highly desirable and were rapidly incorporated into European interiors. Asian artisans responded by producing objects specifically for the European market. East-Asian objects also began to be adapted, dismembered and remounted by European artisans, to suit European customs and perceptions. Furthermore, objects started to be made in Europe in emulation of East-Asian materials, surfaces and motifs.

In his recently published book entitled Borrowed Landscapes Emile de Bruijn charts the taste for things Chinese and Japanese in the British Isles between 1600 and the twentieth century. The historic houses in the care of the National Trust in England, Wales and Northern Ireland contain numerous objects, decorative schemes and structures that are either genuinely East-Asian or were inspired by ‘the East’. This is the first time that this aspect of the National Trust’s collections has been highlighted in a substantial publication. Many of the objects featured were researched and photographed specifically for this project.

The author has tried to define certain mechanisms and trends that these diverse objects and decorations have in common. He uses the concept of ‘orientalism’ as defined by Edward Said in his eponymous 1978 book, in this case applying it specifically to the Western perspective on East Asia. Through the chronological narrative of the book, it becomes evident that certain processes occurred repeatedly, such as the tendency to fictionalise ‘the East’, to domesticate East-Asian elements in European settings, to create Western definitions of East-Asian cultural phenomena and to prefer European orientalised imagery to the reality of East Asian. At the same time, a fascinating change can also be discerned over time, from a relative lack of concern for authenticity in the seventeenth century to a great interest in what was considered to be authentic Chinese and Japanese taste in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Although this book focuses on historic interiors and gardens in the British Isles, the ‘orientalist’ cultural phenomenon it describes was of course also developing elsewhere in Europe. The book documents some of the National Trust’s holdings in this area and contribute to the wider discussion about the cultural interactions between Europe and East Asia and about the role of fiction in culture.

For further information about the book write emile.debruijn@nationaltrust.org.uk